Do Infants Require Less Supramaximal Ulnar Nerve Current? The Answer May Surprise You

Kalli’s study from 1989 suggests it’s very similar.

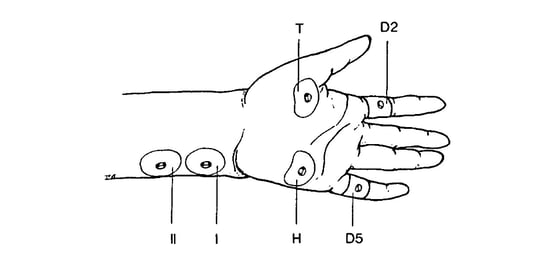

Figure 1. Illustration from I. Kalli showing recording electrodes over the adductor pollicis (T=thenar) and the abductor digiti minimi (H=hypothenar). D2 and D5 are ground electrodes.

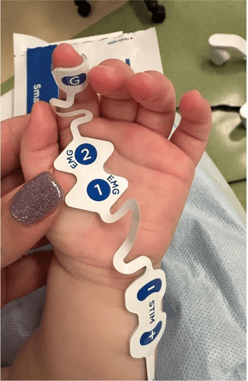

There is growing interest in routine quantitative neuromuscular block monitoring in infants and small children. The availability of small single-piece electrode arrays for electromyography will undoubtedly facilitate this practice.

Figure 2. A small TwitchView electrode array on an infant.

I do not take care of infants or children, so I do not have clinical experience with neuromuscular block monitoring in these patients, but as a researcher in this field, I have often wondered whether there is any difference in the ulnar nerve stimulating current that is required in tiny children compared to adults.

All of the quantitative neuromuscular block monitors that I know of determine the “supramaximal” current by administering a stepwise series of increasing currents until the amplitude of the twitch response becomes maximal. Then an additional amount of current is added (supramaximal) as a safety margin, to be sure that the ulnar nerve is being adequately stimulated. This procedure has to be carried out after the patient is asleep but BEFORE administering a neuromuscular blocking drug. Alternatively, the operator may simply select the highest possible current, which is usually in the range of 60-80 mA, depending upon the particular monitor.

It turns out that there was a beautiful study of this in infants performed by I. Kalli and published in the British Journal of Anesthesia in 1989. It was a small study of 5 infants ranging from 14 days to 4.7 months of age, and 5 children ranging from 1 to 10 years of age, but it was thorough.

Kalli reported that the supramaximal current was 40-70 mA. This is the same range of supramaximal current that we would expect in older children or adults. So based on Kali’s work, it appears that we can utilize the automatic supramaximal current determination of the available quantitative neuromuscular block monitors in infants and small children, just as we would in older children or adults. Obviously, this is great “news” (36-year-old news!)

Figure 3. Peak-peak amplitude of evoked response versus age (on a log scale) for the adductor pollicis (top) and the abductor digiti minimi (bottom) from I. Kalli.

Figure 3. Peak-peak amplitude of evoked response versus age (on a log scale) for the adductor pollicis (top) and the abductor digiti minimi (bottom) from I. Kalli.

Another finding was that the peak-to-peak amplitude recorded at the adductor pollicis or abductor digiti minimi increased with age, presumably related to the maturation of the neuromuscular junction with age (Figure 3).

Kalli also observed that because of the small size of the wrist, unintended stimulation of the median nerve sometimes occurs. It is important in children and adults to be sure that the stimulating electrodes overlie the ulnar nerve, which is closer to the edge of the forearm than many people realize. Placing the stimulating electrodes near the center of the forearm in children or adults may not result in optimal ulnar nerve stimulation.

I’ve only hit the high points of Kalli’s study. I urge you read the entire paper if this topic is of interest to you. It’s a great example of the fact that “old” literature can be very valuable. Recent studies are not always better studies.

Adapted with permission from Andrew Bowdle MD, PhD, FASE. Originally published on Dr. Bowdle's Substack

A Higher Plane of Anesthesia.

- Kaufhold N, Schaller SJ, Stäuble CG, Baumüller E, Ulm K, Blobner M, Fink H. Sugammadex and neostigmine dose-finding study for reversal of residual neuromuscular block at a train-of-four ratio of 0.2 (SUNDRO20)†, Br J Anaesth. 2016 Feb;116(2):233-40.

- Fuchs-Buder T, Meistelman C, Alla F, Grandjean A, Wuthrich Y, Donati F. Antagonism of low degrees of atracurium-induced neuromuscular blockade: dose-effect relationship for neostigmine. Anesthesiology. 2010 Jan;112(1):34-40.

- Kim KS, Cheong MA, Lee HJ, Lee JM. Tactile assessment for the reversibility of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade during propofol or sevoflurane anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004 Oct;99(4):1080-1085.

- Ebert TJ, Cumming CE, Roberts CJ, Anglin MF, Gandhi S, Anderson CJ, Stekiel TA, Gliniecki R, Dugan SM, Abdelrahim MT, Klinewski VB, Sherman K. Characterizing the Heart Rate Effects From Administration of Sugammadex to Reverse Neuromuscular Blockade: An Observational Study in Patients. Anesth Analg. 2022 Oct 1;135(4):807-814.

- Herbstreit F, Zigrahn D, Ochterbeck C, Peters J, Eikermann M. Neostigmine/glycopyrrolate administered after recovery from neuromuscular block increases upper airway collapsibility by decreasing genioglossus muscle activity in response to negative pharyngeal pressure. Anesthesiology. 2010 Dec;113(6):1280-8.

- Payne JP, Hughes R, Al Azawi S. Neuromuscular blockade by neostigmine in anaesthetized man. Br J Anaesth. 1980 Jan;52(1):69-76.