A Guide to Muscle Recovery from Neuromuscular Blocking Agents

Get a Printable Guide to Relative Muscle Recovery from NMBAs

The Variability of Muscle Response to Neuromuscular Blocking Agents

The effects of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs), including their onset and duration of action, differ throughout the body [1]. Biological factors such as acetylcholine receptor density and concentration, fiber composition, innervation ratio and blood flow all influence how a muscle responds to relaxants [2]. External factors like temperature and anesthesia technique can also impact the muscle's response leading to variable recovery rates during surgery.

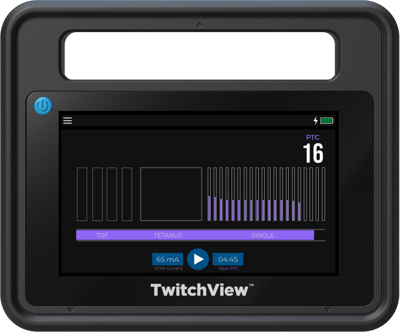

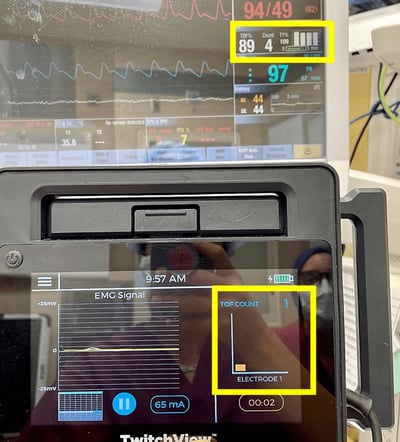

Continuous data from quantitative neuromuscular monitors provides real-time insights into the individual patient’s neuromuscular response and can guide NMBA dosing intraoperatively. The ASA and ESAIC guidelines recommend monitoring the adductor pollicis, but how does the thumb relate to the rest of the body? By applying comparative sensitivity and relative recovery rates of various muscle groups, providers can use data from the thumb to maintain optimal surgical conditions.

Using Quantitative TOF Monitoring to Maintain Optimal Surgical Conditions

Listed below are several muscle groups ranked from the most resistant and quickest to recover from NMBAs to the least resistant and last to recover:

Diaphragm

The diaphragm exhibits the greatest resistance to NMBAs, requiring 1.5-2 times more muscle relaxant than the adductor pollicis (AP) to achieve comparable levels of relaxation. Additionally, the diaphragm experiences quicker onset and recovery times than the AP [2]. This difference may be attributed to enhanced blood flow within the diaphragm, which results in a higher initial concentration and more rapid clearance of NMBAs at the neuromuscular junction [1, 3].

Laryngeal Muscles and Vocal Cords

The larynx including the vocal cords is more resistant with a faster onset and offset of NMBA’s effects [1]. Given the quicker response at the vocal cords, waiting until the train-of-four count (TOFC) reaches 0 on the AP should not be necessary to achieve optimal intubating conditions. While the larynx is located within the upper airway, its response to NMBAs most closely resembles the diaphragm—not the pharyngeal muscles.

Corrugator Supercilii

Recovery data on the corrugator supercilii (eyebrow) and the orbicularis oculi (eyelid) are often conflated in the literature. Eyebrow twitches as a result of facial nerve stimulation are aligned with the diaphragm, characterized by quick onset and recovery, as well as increased resistance to NMBAs [3, 4].

Abdominal Muscles

The onset and recovery from neuromuscular blocking agents is slower in the abdominal muscles than in the diaphragm but faster than the adductor pollicis [5, 6]. Like the diaphragm, movement of the abdominal muscles is possible when a TOFC 0 is measured at the AP [4]. No studies have directly compared the response times of the abdominal and facial muscles.

Orbicularis Oculi

The orbicularis oculi muscle, which is responsible for eyelid blinking, has a recovery rate that is more similar to that of the ensuing hand muscles. However, it can be challenging to differentiate orbicularis oculi activity from that of the corrugator supercilii in clinical practice. Assessments of the facial muscles and hand muscles are not interchangeable, and the observed response to facial nerve stimulation should not be used to determine appropriate reversal or recovery from neuromuscular blockade [3, 4].

This video depicts the depth of blockade that aligns with preliminary recovery in four main muscle groups. Expect signs of recovery when the muscle group lights up. Relative to the adductor pollicis, commonly assessed muscles like those of the eye recover at a faster rate. It is not uncommon for the diaphragm to trigger breaths while the AP is in PTC

Abductor Digiti Minimi

The abductor digiti minimi (pinky) recovers faster than the adductor pollicis, indicating a relative resistance to neuromuscular blockade. Data from the abductor digiti minimi underestimates the patient’s degree of blockade and overestimates recovery and should not be used to determine extubation timing. As stated in the ASA Guidelines:

Data from the abductor digiti minimi muscle should be used with caution to guide neuromuscular blockade management (understanding the patient is more deeply paralyzed than the monitor indicates).

Flexor Hallucis Brevis

Data on the recovery rate of the flexor hallucis brevis muscle in the foot are inconsistent, some results indicating alignment with the AP and others demonstrating a slightly faster recovery [7, 8]. However, recovery timing is more similar between the adductor pollicis and flexor hallucis brevis than between adductor pollicis and the facial muscles. Stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve and the measured response of the flexor hallucis brevis is considered a clinically useful alternative when the hand is inaccessible [7, 8, 9].

Adductor Pollicis & First Dorsal Interosseous

The adductor pollicis (AP) is the reference site for patient recovery. The sensitivity and timing of the effects of NMBAs on the AP align closely with the upper airway muscles [3]. Simultaneous TOF ratios (TOFRs) of the AP and first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscles are interchangeable making both the AP and FDI reliable indicators of airway status [7].

Masseter Recover

The recovery rate of the masseter and the adductor pollicis are similar [2, 10]. The masseter supports a patent upper airway by positioning the mandible. In a study on clinical symptoms of residual paralysis in awake volunteers, study participants could not prevent a wooden tongue depressor from being dislodged from clenched incisors until their TOFR > 86% [10].

Upper Airway

Concerning their response to NMBAs and risk for residual paralysis, the upper airway consists of the airway dilator muscles like the geniohyoid and genioglossus (tongue) and the pharyngeal muscles. The upper airway muscles are among the most sensitive to NMBAs exhibiting the slowest recovery [1, 2, 5, 6, 7]. Consequently, upper airway obstruction is commonly seen in patients with residual paralysis—even at minimal and shallow levels of block (TOFR 50-80%) [10]. In addition to maintaining an open airway, the aforementioned upper airway muscles assist in the clearance of secretions and regurgitated stomach content following anesthesia. With a train-of-four ratio less than 90% measured at the AP, there is a decrease in upper esophageal tone, increasing the risk of aspiration [6].

This video depicts the depth of blockade when adequate recovery is achieved at the upper airway. The upper airway including the airway dilator muscles and the pharyngeal muscles are sensitive to NMBAs and recover slower than the diaphragm and commonly assessed facial muscles. The sensitivity and recovery of the adductor pollicis and first dorsal interosseous align with the upper airway and adequate recovery is defined as a TOFR of ≥90%.

Why is monitoring recommended at the adductor pollicis?

A smooth and rapid post-operative recovery depends on the patient’s ability to breathe. Respiration requires the upper airway muscles to contract in synchrony with the diaphragm, but they’re on opposite spectrums of the recovery scale [6]. Utilizing a muscle (the adductor pollicis) that resembles the recovery rate of the upper airway muscles reduces the likelihood of overdosing NMBAs and allows for confidence in the patient’s complete recovery [2].

Want to implement quantitative train-of-four monitoring at your hospital?

- Kopman, A. F. (2011). Perioperative Monitoring of Neuromuscular Function. In Monitoring in Anesthesia and Perioperative Care(pp. 261–280). Cambridge University Press.

- Viby-Mogensen J. (2001). Neuromuscular monitoring. Current opinion in anaesthesiology, 14(6), 655–659.

- Donati, F., Meistelman, C., & Plaud, B. (1990). Vecuronium Neuromuscular Blockade at the Diaphragm, the Orbicularis Oculi, and Adductor Pollicis Muscles. Anesthesiology, 73(5), 870–875.

- Donati, F. (2012). Neuromuscular Monitoring: More than Meets the Eye. Anesthesiology, 117(5), 934–936. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e31826f9143

- Abu Elyazed, Mohamed & Abdelkhalik, Sameh. (2019). Deep versus moderate neuromuscular block in laparoscopic bariatric surgeries: effect on surgical conditions and pulmonary complications. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 35. 51-58. 10.1080/11101849.2019.1625506.

- Krassen Kirov, Cyrus Motamed, Gilles Dhonneur; Differential Sensitivity of Abdominal Muscles and the Diaphragm to Mivacurium: An Electromyographic Study. Anesthesiology2001; 95:1323–1328

- Stephan R. Thilen, Wade A. Weigel, Michael M. Todd, Richard P. Dutton, Cynthia A. Lien, Stuart A. Grant, Joseph W. Szokol, Lars I. Eriksson, Myron Yaster, Mark D. Grant, Madhulika Agarkar, Anne M. Marbella, Jaime F. Blanck, Karen B. Domino; 2023 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Monitoring and Antagonism of Neuromuscular Blockade: A Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Neuromuscular Blockade. Anesthesiology 2023; 138:13–41

- Michael J. Sopher, Daniel H. Sears, Leonard F. Walts; Neuromuscular Function Monitoring Comparing the Flexor Hallucis Brevis and Adductor Pollicis Muscles. Anesthesiology1988; 69:129–131

- Le Merrer, Maëlle; Frasca, Denis; Dupuis, Maxime; Debaene, Bertrand; Boisson, Matthieu. A comparison between the flexor hallucis brevis and adductor pollicis muscles in atracurium-induced neuromuscular blockade using acceleromyography: A prospective observational study. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 37(1):p 38-43, January 2020.

- Aaron F. Kopman, Pamela S. Yee, George G. Neuman; Relationship of the Train-of-four Fade Ratio to Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Residual Paralysis in Awake Volunteers . Anesthesiology1997; 86:765–771

- Eikermann M, Vogt FM, Herbstreit F, Vahid-Dastgerdi M, Zenge MO, Ochterbeck C, de Greiff A, Peters J. The predisposition to inspiratory upper airway collapse during partial neuromuscular blockade. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Jan 1;175(1):9-15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1862OC. Epub 2006 Oct 5. PMID: 17023729.